The incomes of the poorest are rising at a faster pace than any time since January 2015. That could be the reason for Modi winning elections and why the growth slowdown will soon reverse.

In a highly personalised attack on Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, (‘I need to speak up now’, IE, September 27) ex-Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha made the following claims about the Indian economy (under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi). First, that the economy was on a downward spiral; second, that “demonetisation has proved to be an unmitigated disaster”; third, that GST was badly conceived and implemented; fourth, extra jobs have been lost under Modi-Jaitley; fifth, there was no hope for recovery, especially with Jaitley as FM. He ends this vitriolic piece with a flourish — “the PM claims that he has seen poverty from close quarters. His FM is working over-time to make sure that all Indians also see it from equally close quarters”.

Sinha raises some serious questions about the economy, and as an ex-finance minister, his views have to be taken seriously. Sinha has also been accorded cult status and some are openly talking about him being the face of the opposition (to Modi) in the 2019 elections.

What are the economic facts mentioned by Sinha to support his conclusions? He mentions that the GDP growth rate was 5.7 per cent in 2017Q2; in addition, that “according to the old method of calculation, the growth rate of 5.7 per cent is actually 3.7 per cent or less”. Sadly, the IMF-UN-World Bank mandated national accounts methodology has become something that the political opposition has used to discredit the Modi government. But until Sinha’s column, the Opposition had refrained from questioning the 5.7 figure — it was low enough to be critical of government management, so why bother?

But is Sinha right about the 3.7 per cent? The main criticism about the new GDP figures was that the estimates of industrial production (derived from the Ministry of Corporate Affairs data) were at sharp variance with those traditionally derived from IIP data. In 2017-Q2, GDP data has industrial production growth at 1.6 per cent, and the IIP figures for the same quarter show a higher average of 1.9 per cent growth. Maybe we should hold the CSO to task for deliberately, and maliciously, understating GDP growth — as friends of Sinha (like former FM P. Chidambaram) accused the CSO for overstating GDP growth earlier.

Many have claimed, like Sinha, that demonetisation was an unmitigated disaster, but no one has provided any evidence to prove the same. As far back as November 19, 2016, just 11 days after the announcement of demonetisation (‘Big bang or big thud’,IE), I began by stating that: “By the strangest of coincidences, those opposing demonetisation are almost 100 per cent of those who have opposed every economic decision of this government since day one.” I went on to state that whether demonetisation was a success or not should not be measured by how much cash was returned. Over 99 per cent of the cash has been returned and many observers proudly proclaim: There, we told you so — demonetisation inflicted pain for no gain. And excess pain on the poor poor. The poor then, because of this pain, went and voted for Modi in overwhelming numbers. Let us be honest — yes, demonetisation was a disaster for those who evade taxes.

The jury on whether demonetisation would lead to a jump in tax revenues is still out; if demonetisation does not lead to an increase in personal income tax compliance, then yes, it did not work. Tax compliance in India is at low 25 per cent —. for every Rs 100 of income tax that the government should collect, it collects only Rs 25. Some critics have looked at the confusing set of numbers on those who have filled tax returns this year, relative to the pre-demonetisation earlier year. This is not the complete, or even a quarter of the tax compliance story. Look at increase in tax revenues, relevant to an increase in income growth, for knowledge, and inference, and conclusion about the efficacy of demonetisation.

Yet another Sinha complaint is that GST has been a disaster. This is very strange — one of the biggest reforms in India is barely two months old and we already have evidence that it was badly implemented and a conceptual failure? No doubt there are several problems with GST — the average GST tax rate is too high and tax credits are not being delivered in time. And one can add several layers of worthy criticism. But to pronounce it a failure for 15 minutes of Warhol time is not, well, worthy of an ex finance minister.

Moving on — I have also criticised policies for the slowdown, in particular the exorbitantly high real interest rate policy followed by the MPC. During Sinha’s FM tenure (1999-2002), the real RBI call rate declined by 200 basis points. During Jaitley’s tenure (2014-2017) the real repo rate has increased by 200 bp. I don’t see the slowdown as structural — I see it as a self-inflicted cyclical, easily reversible wound which might begin to repair as early as next week.

One further point on the uncompetitive nature of our monetary policy. The increase in the real repo rate in India (average increase over 36 months earlier) during the last 21 months is the second highest among major emerging markets. Our increase is at 370 bp, Russia at 500 bp, Brazil at 300 and Indonesia some distance behind at 182 bp.

I want to end with the following puzzle to several critics, and supporters, of the government: There is a lot of anecdotal evidence about the poor, and not so poor, losing their jobs because of demonetisation and other Sinha-articulated bad policies of the government. If the poor are really losing out, it should show up in the rate of growth of real wages (some political ideologues actually point to slow growth in nominal wages as evidence that the economy is doing badly — even Sinha does not do that).

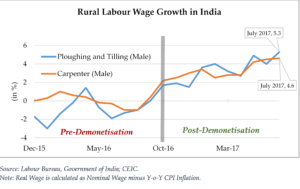

The most unskilled worker in India is the ploughman; with some skills, is the carpenter. If there are jobs being lost in urban areas (MSMEs etc.) the impact should show up in the slowing real wage growth of ploughmen and carpenters. But the opposite is happening. The chart divides the time-period since December 2015 into two sections — before and post-demonetisation. At the time of demonetisation, real wages were rising at 2 per cent per annum. Post demonetisation, in July 2017, the rate of growth has more than doubled to near 5 per cent.

If these data are correct (maybe the dataratti will now move towards questioning the accuracy of the rural wage data, the oldest such series in India) then the incomes of the poorest are rising at a faster pace than any time since January 2015. Maybe that is why Modi has been winning elections; maybe that is why the growth slowdown (with a little help from the RBI) will soon reverse.

Over the last 20 years, I have written close to a thousand op-ed pieces. I have presented data with my arguments, and when I make data mistakes (thankfully, very few), readers have corrected me. My plea to my fellow columnists, and the media, and the economists, and to politicians, and to everybody — let us get real, and debate evidence, and debate how to interpret the facts. Let us not decline into ideology, and worse, into personal attacks. The economy should not be treated like a gossip column.